Not “Cavalier” About Climate Change: Leading the University of Virginia into a Carbon-Neutral Future

Share

As universities around the world take the lead in advancing climate action, the transition to carbon-neutral energy systems has become not just an environmental imperative, but an opportunity for long-term operational resilience. For the University of Virginia (UVA), achieving carbon neutrality by 2030 and eliminating fossil fuel use by 2050 represents a significant challenge—one that requires innovative approaches to energy infrastructure and an actionable plan.

To turn this vision into reality, UVA partnered with Ballinger and FVB to develop the Strategic Thermal Energy Study (STES), a flexible, technically robust, and financially feasible framework for campus decarbonization. UVA’s phased strategy is not just a blueprint for their 550-building, 18 million GSF campus—it’s a model for any large institution grappling with the complexities of energy transition. By focusing on future-readiness, our team’s approach ensures that the investments made today will yield operational, financial, and environmental dividends for decades to come.

Saying Goodbye to Steam

According to Ballinger Associate Principal Mike Radio, PE, CEM, BEMP, LEED AP BD+C, creating the STES involved analyzing three phased scenarios, each representing a different level of phase out for the existing fossil fuel-based central campus steam system. “The scenarios included future optionality for implementation of developing technologies such as green hydrogen or other renewable fuels,” he said, “But central to each scenario is the goal of significantly diminishing the steam distribution system with a phased transition to low temperature hot water (LTHW).”

Prior to developing the STES, UVA had already begun converting its heating systems to hot water. Stress tests revealed that most buildings could be heated with 140°F water, although some historic buildings, over 200 years old, required 160°F. The building with the highest temperature requirement dictated the temperature for the entire heat loop. Meanwhile, UVA installed an 1,800-ton heat recovery chiller capable of generating 170°F water for simultaneous heating and cooling. To enhance efficiency, our team developed a conversion strategy to gradually transition all buildings to 140°F, improving the chiller’s performance and enabling future upgrades in the low-temperature loop.

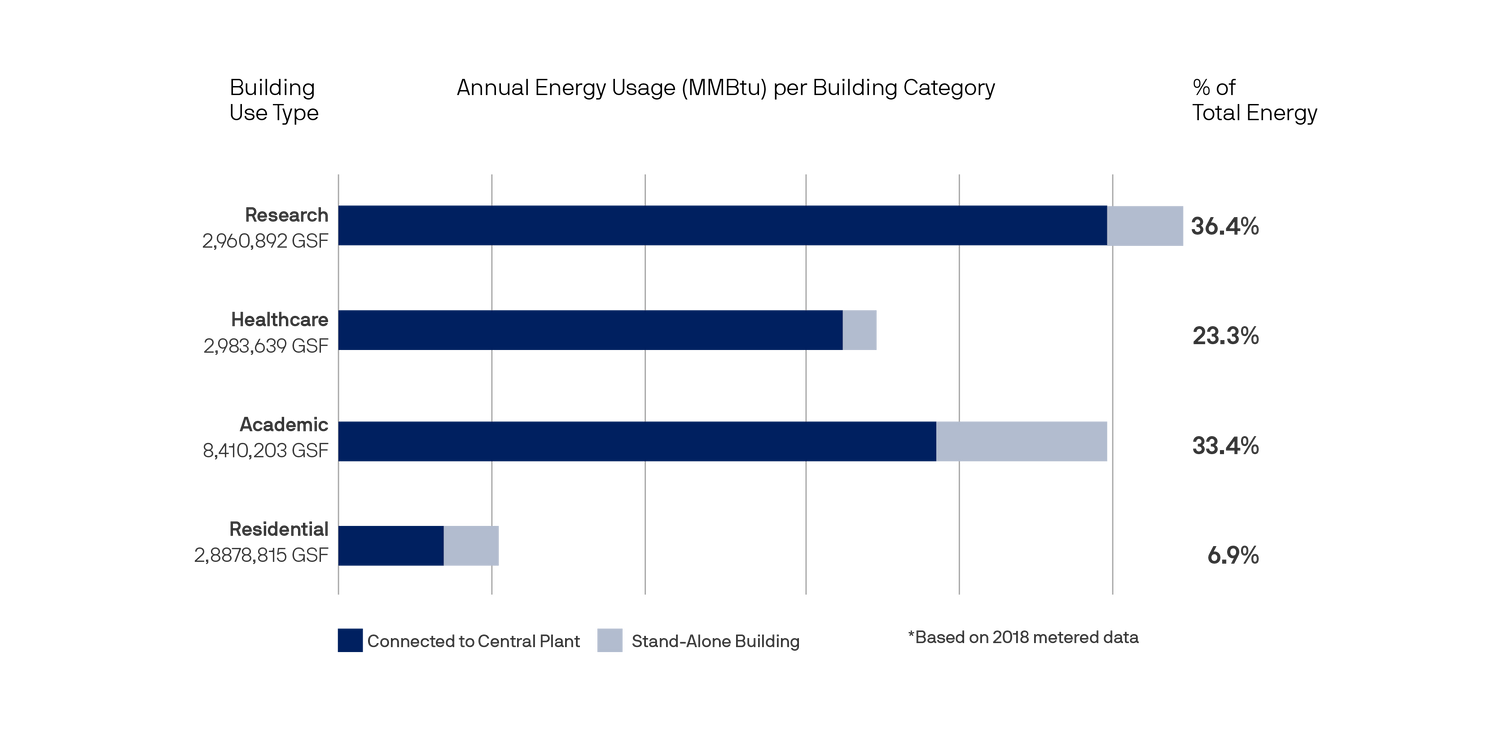

Although research and healthcare buildings make up only 34% of the campus’ gross square footage (GSF), they account for nearly 60% of its annual energy consumption.

A Bigger, Brighter Future

While progress had already begun on converting heating systems, research and healthcare buildings posed unique challenges due to their heavy reliance on process steam and humidification. To navigate these complexities, a phased plan was introduced to decommission equipment like autoclaves and sterilizers as they reach the end of their service life. This approach maximizes the value of past investments while creating opportunities for future technological advancements that align with electrification requirements.

Throughout the development of the STES, Ballinger collaborated closely with the University’s Office of the Architect, Office of Sustainability, and other key stakeholders to evaluate future building growth scenarios and their impact on infrastructure capacity. Together, the team developed guiding principles that incorporate high-performance design strategies and energy performance targets for all new construction. In addition, a targeted approach was created to implement strategic upgrades for existing building systems, focusing on high-energy-consuming facilities (EUI 300 or greater) nearing system obsolescence.

By aligning new building standards with strategic conversions, the plan enables a reduction in annual heating energy consumption by 2050, even as the total building square footage on campus increases by over six million GSF.

Harnessing Data

In Part 2 of this series, “Data is the New Green,” we explored how UVA’s digital twin energy model played a pivotal role in managing vast amounts of data from over 500 buildings. This model was key to evaluating carbon reduction scenarios across both existing and new infrastructure. By visualizing the financial impacts of various decarbonization strategies, including energy savings, operational costs, and capital expenditures, the model empowered UVA to make informed decisions that align with long-term sustainability goals. Additionally, the digital twin model can incorporate current weather patterns and predict future climate shifts, helping UVA assess the impact of climate change on its infrastructure and plan accordingly.

Beyond its role in visualizing decarbonization strategies, the digital twin model also played a critical part in evaluating the financial implications of these approaches. A decarbonization plan of this magnitude comes with significant financial considerations, and we worked closely with UVA to assess both short-term and long-term costs of transitioning away from fossil fuels. This included examining the financial viability of alternative energy sources, the potential savings from reduced energy consumption, fuel and electricity price forecasting, and the initial costs of upgrading infrastructure.

In addition to evaluating costs, the financial assessment also informed UVA’s exploration of electrifying its heating systems, a critical component of the decarbonization plan. As part of this effort, our team analyzed the capacity of on-site electrical distribution systems and Dominion Power’s regional grid to handle the increased demand. This shift could place added strain on the grid, particularly during peak winter usage. However, using the digital twin model, the STES demonstrated that strategic building upgrades would prevent winter electric peak demand from exceeding summer levels.

A Geoexchange of Ideas

At the same time, our team explored the feasibility of installing geothermal systems to further reduce reliance on fossil fuels. We assessed both the technical and financial aspects of the project, considering factors such as local geology, land availability, and building proximity. Each scenario examined varying levels of geoexchange boreholes paired with heat pump chillers. While UVA cannot decarbonize their entire campus with geothermal alone due to land constraints, the STES has guided the university toward developing a new geoexchange thermal plant in the Fontaine Research Park District, unlocking significant future decarbonization potential.

While the exploration of geothermal systems revealed new decarbonization opportunities, successfully implementing these strategies required collaboration and consensus-building among multiple stakeholders. “Achieving campus-wide carbon neutrality isn’t just a technical challenge,” said Mike, “it also involves engaging university leadership, faculty, students, and the local community.” To facilitate this, our team played a key role in building consensus by organizing workshops, presentations, and collaborative sessions. This open dialogue allowed stakeholders to understand the long-term benefits of carbon neutrality and participate in shaping the plan. By using digital twin simulations, our team could visually demonstrate the benefits and trade-offs of various decarbonization strategies to stakeholders. These interactive models helped clarify complex concepts, making it easier to communicate the potential impacts of different energy scenarios and gain support for the proposed pathways.

As institutions like UVA pave their way to achieving carbon neutrality, the question for other universities and large organizations becomes: How prepared are you for the energy transition? At Ballinger, we believe that flexible, adaptive frameworks like the STES are key to ensuring long-term resilience in the face of climate change. The future is here—how will your institution rise to the challenge?